Some cases stick because of one hauntingly human detail. In this one, it was a pair of bright orange socks found on a young woman.

True Crime Weekly is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

On Halloween morning in 1979, motorists on Interstate 35 were unknowingly passing the scene of a crime that would go cold for nearly 30 years before DNA evidence could even be tested.

The Morning of Discovery

A driver in Georgetown spotted what looked like bedding debris near a highway drainage opening. When police arrived, they found the body of a young woman inside the culvert opening, partially obscured but not carefully hidden.

Early assessments by investigators determined:

* She had been strangled (primary cause of death)

* She had suffered sexual assault

* She had been beaten particularly around the face and torso

* She had defensive wounds on her hands and arms, showing this wasn’t passive

* There were no illegal substances in her system meaning she was alert, aware, and likely pleading for her life during part of the encounter

For 40 years, she was only known as “Orange Socks,” a nameless victim found in a drainage culvert outside Georgetown, Texas.

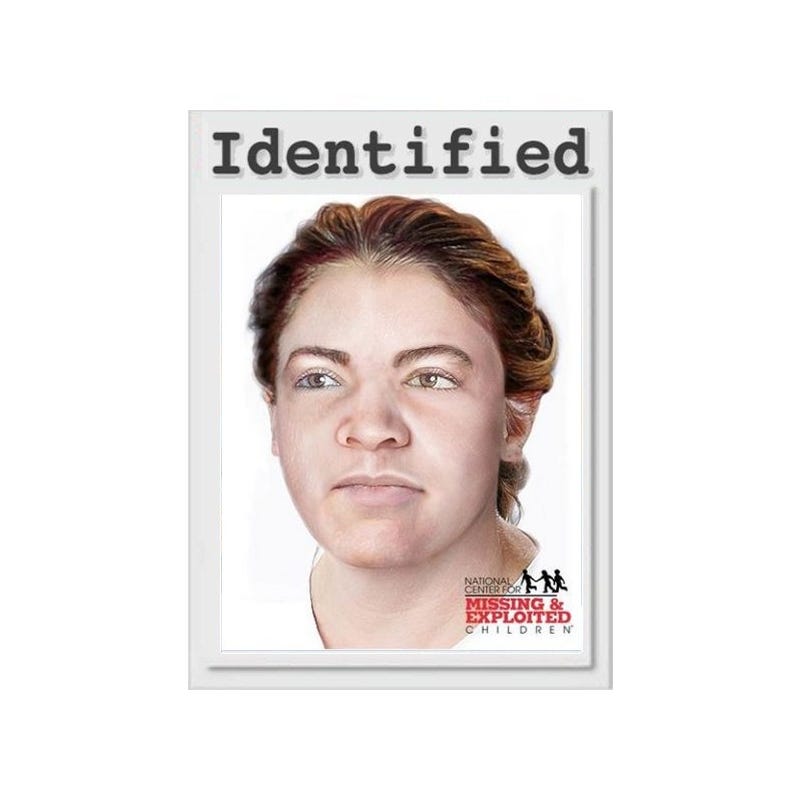

On August 6, 2019, cold-case investigators announced that DNA evidence matched through genealogical databases had identified her as 23-year-old Debra Louise Jackson originally from Abilene, Texas.

Her identity was confirmed after a surviving sister recognized a new forensic sketch of “Orange Socks,” reached out to police, and submitted a DNA sample. That match finally gave the woman found in 1979 the name she’d lost.

Debra had left Abilene in 1977. In 1978 she worked at a Ramada-style hotel in Amarillo, then at an assisted-living facility in Azle, near Fort Worth, when she seemingly drifted and was never reported missing.

The Crime Scene

The body had been found on October 31, 1979 (or possibly late Oct 30), by a motorist who spotted what looked like bedding debris along Interstate 35 near Georgetown, TX.

The young woman was found nude except for a pair of orange socks the mark that gave her the “Orange Socks” nickname.

Autopsy findings confirmed:

* Strangulation as cause of death.

* Evidence of sexual assault and physical trauma

* Defensive wounds she had fought back.

Her body was dumped into a drainage culvert, near a highway a brutal disposal, but one that seemed to presume she would never be identified.

The Breakthrough

In 2018, investigators revisited the case and submitted DNA evidence from the victim to the DNA Doe Project and made a public push for renewed tips.

Then, after a newly released forensic sketch caught the attention of Debra’s sister, the family submitted a DNA sample. The match came back positive via genealogical database comparison.

At last the woman once reduced to a pair of orange socks, a sketch, and a case file had a name again.

True Crime Weekly is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The Murder Still Stands as Unsolved

* No suspect has ever been charged.

* No definitive DNA profile from the killer though investigators reported that male DNA was recovered from under Jackson’s fingernails.

* Previous confession is unreliable. Henry Lee Lucas once confessed to the murder but there’s strong evidence he was elsewhere at the time and may have falsely admitted to many killings.

* No credible eyewitness testimony or contemporaneous leads have withstood scrutiny.

As recently as October 31, 2023 investigators renewed public appeals for information nearly 44 years after her death.

The call: anyone who knew Debra from Abilene, Amarillo, or Azle between 1977–1979 or anyone with even the slightest memory of someone matching her description to come forward.

Giving Debra Jackson her real name meant more than solving a cold case it gave a family closure on one long-lost sister, and transformed “Orange Socks” from ghost to person.

But it also reopened painful questions:

* Who took Debra’s life?

* Why did she leave Abilene and where was she truly headed?

* Why was she never reported missing?

* Who was the man whose DNA remains unidentified?

* Are there others other victims connected to the same killer or pattern?

This isn’t just “case closed.”

Debra’s story troubles me deeply, because it shows what happens when someone becomes “just another Jane Doe.” For decades, she had no name, no memory, no mourners. But now she has a name her family can mourn her properly. And the case, cold for so long, is alive again.

To anyone who remembers a girl gone from Abilene in the late ’70s or a coworker at a Ramada in Amarillo, or a shift-mate at a care facility in Azle you may hold the key.

Because sometimes, all it takes to break a cold case is one memory, one call, one detail.

If you know something anything don’t sit on it.

Call the cold-case unit in Williamson County, Texas.

Give Debra and her family the justice that came too late.

And maybe help close the final chapter on Orange Socks Debra Jackson.

Leave a comment