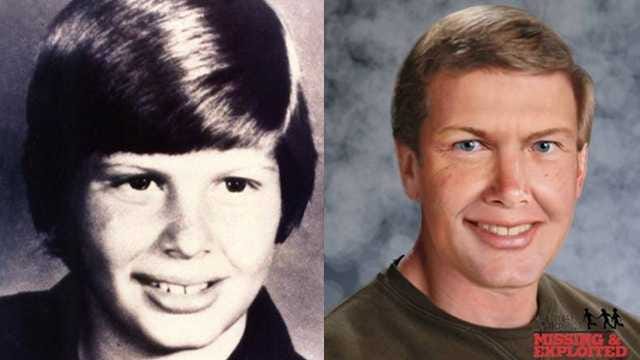

John David Gosch (November 12, 1969 – disappeared September 5, 1982) was a paperboy in West Des Moines, Iowa, United States, who disappeared between 6 and 7 a.m. on September 5, 1982.

He is presumed to have been kidnapped. Gosch’s picture was among the first to be featured on milk cartons as part of a campaign to find missing children. As of 2026, there have been no arrests made; the case is now considered cold but remains open.

True Crime Weekly is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Gosch’s mother, Noreen, claimed that he escaped from his captors and visited her alongside an unidentified man in 1997. She claimed that her son had told her that he had been the victim of a pedophile organization and had been cast aside when he had grown too old but subsequently feared for his life and lived under an assumed identity, feeling it was not safe to return home.

Gosch’s father, John, divorced from Noreen since 1993, has publicly stated that he is not sure whether such a visit actually occurred. Many have also speculated that the visit did occur, but that the visitor was someone else pretending to be Johnny.

Authorities have not located Gosch or confirmed Noreen’s account, and his fate continues to be the subject of speculation, conspiracy theories and dispute.

The case received renewed publicity in 2006 when Noreen reported she had found photographs on her doorstep depicting Gosch in captivity. Some of the photos received were said to be children from a case in Florida; however, one boy in the photos was never identified. Noreen insists that boy is Johnny.

Disappearance

Before dawn on Sunday, September 5, 1982, Johnny Gosch left home to begin his paper route in West Des Moines, Iowa, a suburb of Des Moines proper. Although it was customary for Gosch to awaken his father to help with the route, the boy took only the family’s miniature dachshund, Gretchen, with him that morning.

Other paper carriers for The Des Moines Register would later report having seen Gosch at the paper drop, picking up his newspapers. It was the last known sighting of Gosch that could be corroborated by multiple witnesses.

True Crime Weekly is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Another paperboy named Mike reported that he observed Gosch talking to a stocky man in a blue two-toned car near the paper drop; another witness, John Rossi, saw the man in the blue car talking to Gosch and “thought something was strange.” Gosch told Rossi that the man was asking for directions and asked Rossi to help.

Rossi looked at the license plate, but could not recall the plate number. He said, “I keep hoping I’ll wake up in the middle of the night and see that number on the license plate as distinctly as night and day, but that hasn’t happened.” Rossi eventually underwent hypnosis and told police some of the numbers and that the plate was from Warren County.

As Gosch walked a block north, where his route started, a paperboy noticed he was being followed by another man. A neighbor heard a door slam and saw a silver Ford Fairmont speed away northwards from where Gosch’s wagon was found.

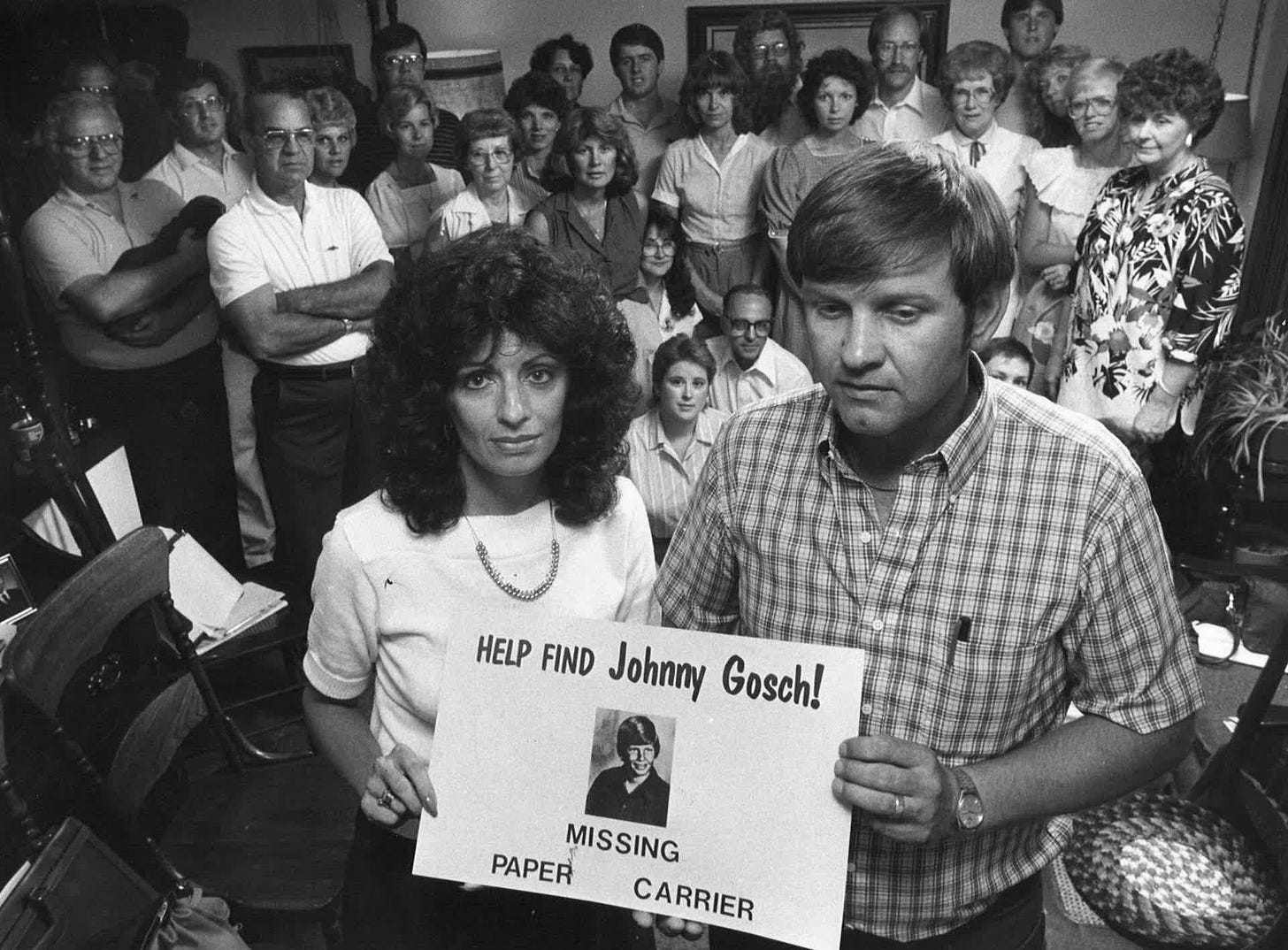

Gosch’s parents, John and Noreen, began receiving phone calls from customers along their son’s route, complaining of undelivered papers. John performed a cursory search of the neighborhood around 6 a.m.

He immediately found Gosch’s wagon, still full of newspapers, two blocks from their home. The Gosches immediately contacted West Des Moines police and reported their son’s disappearance. Noreen, in her public statements and her book Why Johnny Can’t Come Home, has been critical of what she perceives as a slow reaction time from authorities, and of the policy at the time that Gosch could not be classified as a missing person until seventy-two hours had passed. By her estimation, police did not arrive to take her report for a full forty-five minutes.

Police initially assumed that Gosch was a runaway, but later changed their assessment and believed that he had been the victim of a kidnapping. They turned up little evidence and arrested no suspects in connection with the case.

According to Noreen, a few months after his disappearance, Gosch was spotted in Tulsa, Oklahoma, when a boy yelled to a woman for help before being dragged off by two men.

Over the years, several private investigators have assisted Gosch’s parents with the search for their son. Among them are Jim Rothstein, a retired New York City police detective, and Ted Gunderson, a retired chief of the FBI‘s Los Angeles field office.

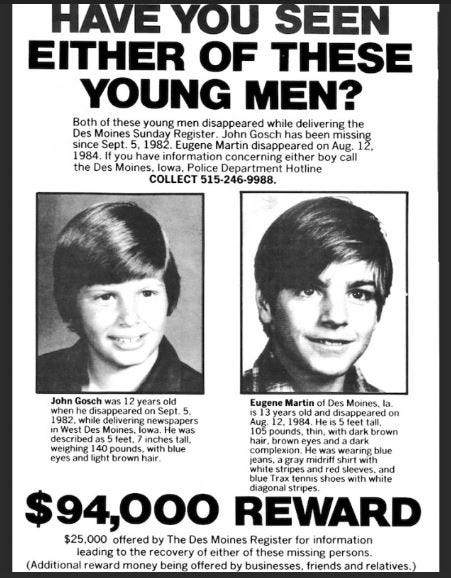

In 1984, Gosch’s photograph appeared alongside that of another Des Moines Register paperboy, Eugene Martin, who had gone missing that year, on milk cartons produced by the Des Moines-based Anderson Erickson Dairy. Gosch was among the first missing children who had their disappearances publicized in this way.

Potentially linked cases

On August 12, 1984, Eugene Martin, another Des Moines-area paperboy, disappeared under similar circumstances.

He went missing while delivering newspapers on the city’s south side. Over a year later, on March 29, 1986, the day before Easter, Marc James Warren Allen disappeared while walking to a friend’s house down the street from his own residence.

Media reports initially described Allen as the third Iowa paperboy to go missing in the 1980s, but a detailed piece about Iowa’s missing people that appeared in the Registeron August 18, 2013, claimed that Allen had never been a paperboy.However, Allen’s brother would later confirm that he was indeed a paperboy, but had not been working on a route at the time of his disappearance.

Authorities were unable to prove a connection between the three cases, yet Noreen claims that she was personally informed of the Martin abduction a few months in advance by a private investigator who was searching for her son. She was told the kidnapping “would take place the second weekend in August 1984 and it would be a paperboy from the southside of Des Moines.”

Fraud by wire case

In 1985, Noreen received a letter from Robert Herman Meier II, aged 19, of Saginaw, Michigan. In the letter, which he had signed under the name of “Samuel Forbes Dakota,” Meier stated that he was a guard in an outlaw motorcycle club at the time of Gosch’s disappearance.

According to Meier, Gosch’s son was taken as part of a large child slavery ring operated by the club. According to the FBI, Meier requested and received $11,000 (about $32,000 in 2023) from Gosch’s parents. He additionally requested $100,000 (about $285,000 in 2023) more along with a promise to return their son.

Meier was arrested at the Canadian border by FBI agents and was later charged with fraud by wire. The letter had stated that Gosch’s son was sold to a man whom Meier identified as a “high-level drug dealer residing in Mexico City.” Despite the accusation of fraud, Noreen reportedly believed Meier at his word and later criticized the FBI, stating that Meier’s arrest destroyed her and her husband John’s credibility with anyone who would take the couple’s offer to pay ransom for their son.

True Crime Weekly is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Noreen Gosch’s account

According to Noreen, in March 1997, she was awakened around 2:30 a.m. by a knock at her apartment door. Waiting outside was Gosch, now aged 27, accompanied by an unidentified man. Noreen said she immediately recognized her son, who opened his shirt to reveal a birthmark on his chest.

“We talked about an hour or an hour and a half”, she claimed. “He was with another man, but I have no idea who the person was. Johnny would look over to the other person for approval to speak. He didn’t say where he is living or where he was going.”

In a 2005 interview, Noreen further claimed, “The night that he came here, he was wearing jeans and a shirt and had a coat on because it was March. It was cold and his hair was long; it was shoulder-length and it was straight and dyed black.”

After the visit, she had the FBI create a composite sketch she says looked like the now-grown Johnny. Noreen self-published a book in 2000 titled Why Johnny Can’t Come Home. The book presents her understanding of what her son went through, based on the original research of various private investigators and her son’s visit.

On September 1, 2006, Noreen reported that she had found photographs left at her front door, some of which she posted on her website. One color photo shows three boys bound and gagged. She claims that a black-and-white photo appears to show twelve-year-old Gosch with his mouth gagged, his hands and feet tied and an apparent human brand on his shoulder. A third photo shows a man, possibly dead, who may have something tied around his neck.

Noreen stated that the man was one of the “perpetrators who molested [my] son.” Noreen later said the first two photos had originated on a website featuring child pornography.

On September 13, an anonymous letter was mailed to Des Moines police.

Gentlemen,

Someone has played a reprehensible joke on a grieving mother. The photo in question is not one of her son but of three boys in Tampa, Florida about 1979–80, challenging each other to an escape contest. There was an investigation concerning that picture, made by the Hillsborough County (FL) Sheriff’s Office. No charges were filed, and no wrongdoing was established. The lead detective on the case was named Zalva. This allegation should be easy enough to check out.

Nelson Zalva, who worked for the Hillsborough County, Florida, sheriff’s office in the 1970s, corroborated the details of the letter were true and added that he also investigated the black-and-white photo in “1978 or 1979,” before Gosch’s disappearance in 1982.

“I interviewed the kids, and they said there was no coercion or touching. … I could never prove a crime,” Zalva says.When asked for proof that this was indeed the same photo from the investigation nearly three decades prior, Zalva could not provide any. According to the documentary film Who Took Johnny (2014), only three boys in the pictures were identified by law enforcement, but not the one thought to be Gosch. Noreen still believes the pictures to be of her son.

True Crime Weekly is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In 1989, twenty-one-year-old Paul A. Bonacci told his attorney John DeCamp that he had been abducted into a sex ring with Gosch as a teenager and forced to participate in Gosch’s kidnapping. DeCamp met with Bonacci and believed he was telling the truth. Noreen later met Bonacci and said he told her things “he could know only from talking with her son.”

Bonacci said that Gosch had a birthmark on his chest, a scar on his tongue and a burn scar on his lower leg; although a description of the birthmark had been widely circulated, information about the scars had not been made public. Bonacci also described a stammer that Gosch had when he was upset.

The FBI and local police do not believe that Bonacci is a credible witness in the case and have not interviewed him. Bonacci’s siblings reported to authorities that he was home at the time of Gosch’s disappearance.

In 2023, Bonacci claimed to know about Gosch’s 1997 visit to his mother, and stated that Gosch had visited him several times. In her 2024 updated edition of Why Johnny Can’t Come Home, Noreen states that she believes child pornographers John David Norman and Phillip Paske were responsible for her son’s abduction

National interest

Gosch’s disappearance generated national interest as Noreen became increasingly vocal about the inadequacy of law enforcement’s investigation into missing children. She established the Johnny Gosch Foundation in 1982, through which she visited schools and spoke at seminars about the modus operandi of sexual predators.

She also lobbied for “The Johnny Gosch Bill,” state legislation which would mandate an immediate police response to reports of missing children. The bill became law in Iowa in 1984, and similar or identical laws were later passed in eight other states.

In August 1984, Noreen testified in U.S. Senate hearings on organized crime, speaking about “organized pedophilia“ and its presumed role in her son’s abduction.

according to her, she began receiving death threats. Noreen also testified before the Department of Justice, which provided $10 million to establish the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children; she was invited to the White House by President Ronald Reagan for the dedication ceremony

Leave a comment